Jane Perlez, amerikai újságíró 1994-ben több napot töltött az AKG-ban, majd cikket írt az iskoláról, mely 1994. május 25-én jelent meg a New York Timesban. A megjelent íráshoz sajnos mindeddig nem fértünk hozzá.

A cikket most megkaptuk ajándékba, az alábbiakban olvasható a másolata.

Hungary Schools Seeking Past Glory

By Jane Perlez

May 25, 1994

When cigarette smoking among the students at a local high school spun out of control, in much the way it often does in the United States, the school administration called a referendum, inviting students and parents to vote.

Should 18-year-olds be allowed to smoke? Should those over 16 be allowed to smoke with parental consent? The vote was yes to the 18-year-olds and no to the younger students. Such a vote would not have been unusual in many American schools. But for Hungary, it was revolutionary.

In Eastern Europe for the past 40 years, education has meant authoritarian rule and confined curriculums intended to mold obedient citizens. In contrast, Hungary’s Alternative High School for Economics is a trailblazer for the notion of liberal education. Here students sprawl on the carpeted halls during study periods, and the dress code allows ponytails — for boys — and T-shirts emblazoned with graffiti more suited to a rock club than a traditional classroom.

Fresh Start at New School

Hungarian schools, renowned before World War II for the quality of their education, include among their graduates John von Neumann, the mathematician, and Edward Teller, the physicist. Now they are trying to recapture glory lost during the Communist era. The Budapest Evangelical Gymnasium, which produced Dr. von Neumann as well as George Lukacs, the Marxist theoretician, reopened five years ago as a high school after decades of academic decline.

About the same time the Gymnasium was reborn, a bearded young educator named George Horn came to believe that the public — despairing over the lamentable state of education — would welcome an experimental school. He had already tried to modernize the program at an existing school but realized that reform of the old was impossible, as with many things in Eastern Europe, and that only a fresh start would work.

After his lengthy negotiations with the fading Communist Government, the Alternative School opened its doors in 1990 in a handsome turn-of-the-century gabled brick building. Nearly 6,000 students applied for 80 places.

„At first this was the only school program that offered something different,” said Mr. Horn, who is now the principal but who dresses in jeans and a work shirt and prefers a more egalitarian title, roughly translated as coordinator. „For example, students study what language they want for as long as they want. Ninety percent of the students will learn a language fluently, 90 percent will get a driver’s license and I hope 75 percent will get into one of the universities.”

Essentially a Private School

The school has grown to 400 students. It offers a distinctive policy of self-discipline, and several other aspects make it novel.

While Mr. Horn does not like to call the school private, it essentially is. The Government contributes an annual subsidy but students must still pay an annual fee, the equivalent of $370, or a little more than the average Hungarian monthly salary.

To attract the best teachers and allow the school to pay them double the standard salary, Mr. Horn persuaded banks and insurance companies to contribute. Each entering class of 90 students includes 30 students whose fees are subsidized by these businesses.

But the most startling difference is in the classroom.

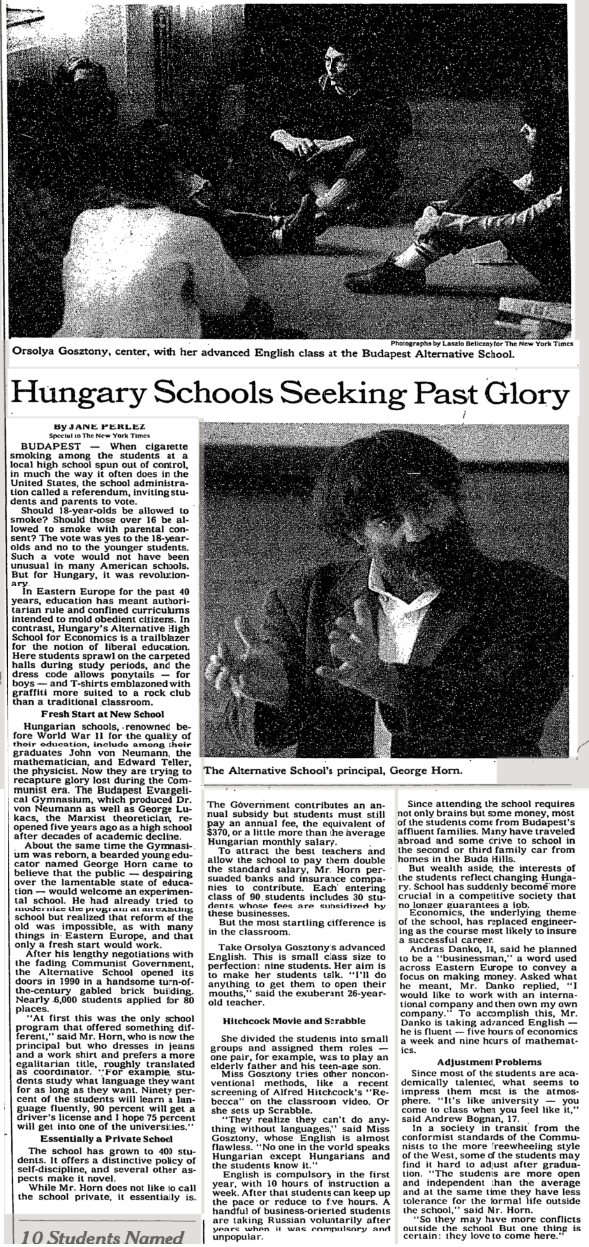

Take Orsolya Gosztony’s advanced English. This is small class size to perfection: nine students. Her aim is to make her students talk. „I’ll do anything to get them to open their mouths,” said the exuberant 26-year-old teacher.

Hitchcock Movie and Scrabble

She divided the students into small groups and assigned them roles — one pair, for example, was to play an elderly father and his teen-age son.

Miss Gosztony tries other nonconventional methods, like a recent screening of Alfred Hitchcock’s „Rebecca” on the classroom video. Or she sets up Scrabble.

„They realize they can’t do anything without languages,” said Miss Gosztony, whose English is almost flawless. „No one in the world speaks Hungarian except Hungarians and the students know it.”

English is compulsory in the first year, with 10 hours of instruction a week. After that students can keep up the pace or reduce to five hours. A handful of business-oriented students are taking Russian voluntarily after years when it was compulsory and unpopular.

Since attending the school requires not only brains but some money, most of the students come from Budapest’s affluent families. Many have traveled abroad and some drive to school in the second or third family car from homes in the Buda Hills.

But wealth aside, the interests of the students reflect changing Hungary. School has suddenly become more crucial in a competitive society that no longer guarantees a job.

Economics, the underlying theme of the school, has replaced engineering as the course most likely to insure a successful career.

Andras Danko, 18, said he planned to be a „businessman,” a word used across Eastern Europe to convey a focus on making money. Asked what he meant, Mr. Danko replied, „I would like to work with an international company and then own my own company.” To accomplish this, Mr. Danko is taking advanced English — he is fluent — five hours of economics a week and nine hours of mathematics.

Adjustment Problems

Since most of the students are academically talented, what seems to impress them most is the atmosphere. „It’s like university — you come to class when you feel like it,” said Andrew Bognan, 17.

In a society in transit from the conformist standards of the Communists to the more freewheeling style of the West, some of the students may find it hard to adjust after graduation. „The students are more open and independent than the average and at the same time they have less tolerance for the formal life outside the school,” said Mr. Horn.

„So they may have more conflicts outside the school. But one thing is certain: they love to come here.”

A version of this article appears in print on May 25, 1994, Section B, Page 9 of the National edition with the headline: Hungary Schools Seeking Past Glory.

Az eredeti, archivált cikk: https://www.nytimes.com/1994/05/25/us/hungary-schools-seeking-past-glory.html